Memling in Bruges

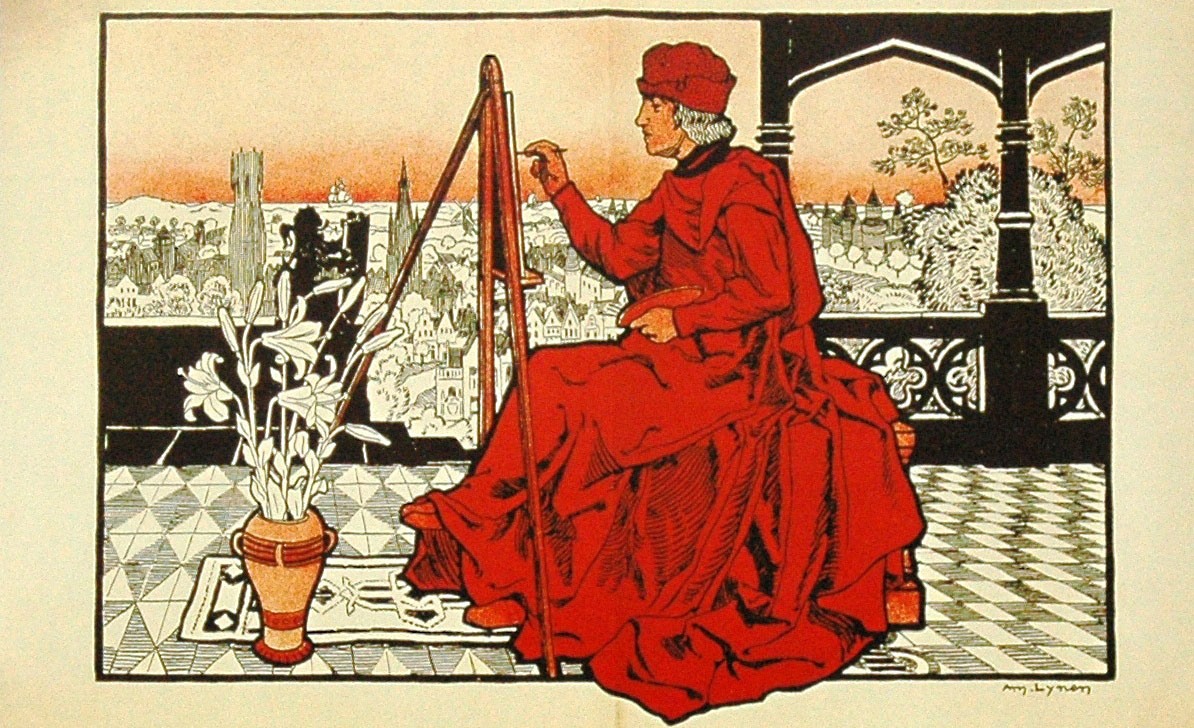

15th century: Arrival

1465: Memling settles in Bruges

In 1465, Hans Memling registers as a citizen at the Poortersloge (Burgher’s Lodge) in Bruges. From that moment, he is a true citizen of Bruges. Admittedly, registration is no easy process: so-called portership has to be approved by the local court (de vierschaar). Moreover, it comes with a price tag of 10% of your assets.

Memling arrives in Bruges at a time when the city lacks great painting talent, despite demand being high. His first big commissions come from abbots and bankers, think of the Last Judgement

(1467– 1471) and The Triptych of Jan Crabbe (c. 1472). Where Memling goes to live also seems to be a conscious choice. He settles in the Jorisstraat, an important hub where he is close to wealthy patrons. For instance, the street is connected to the Beursplein, the commercial heart of Bruges and where the Italian lodges are located. Just west of the Beursplein are the Spanish merchants.

In 1480, he buys the house in the Jorisstraat and a few years later he extends his residence so that he can cope with the influx of so many commissions.

1472: Crabbe triptych

Jan Crabbe was an abbot at the Ten Duinen Abbey of Our Lady. He was also a political advisor and an art lover. He commissioned an altarpiece from Memling, later called the Crabbe Triptych, one of Memling’s earliest works to be dated. In the central panel, Crabbe is portrayed as a patron, kneeling. In the 18th century, the work was sawn into separate panels and sold. As a result, the triptych is not preserved as a whole today. The exterior panels featuring the Annunciation eventually ended up in the Musea Brugge collection.

1479: St John Altarpiece and the Floreins triptych & 1480: Adriaan Reins triptych

In 1479, Memling completed two altarpieces: the St John Altarpiece and the Triptych of Jan Floreins. They are the only works that are dated and signed. Memling made both works at the request of the friars and nuns of the Saint John’s Hospital. The St John Altarpiece is specially made for the main altar in the hospital’s new choir apse. In the same year, Memling paints the triptych with the Adoration of the Magi for the friar Jan Floreins, who later became master of Saint John’s Hospital. The triptych was possibly installed on a side altar in the hospital chapel. In the central panel, Floreins is portrayed praying.

In 1480, Memling paints an altarpiece with the Lamentation for the friar Adriaan Reins. The year and Reins’s initials are painted on the frame of the central panel.

Ca. 1470, 1480 and 1487: Three portraits

One third of Memling’s preserved oeuvre consists of portraits. Three of these are in the Musea Brugge collection. One of these portraits is that of Francisco (?) De Rojas (c. 1470). He is a descendant of an influential Spanish family and ambassador of Spain to the Burgundian court. It is uncertain, however, whether the man portrayed is indeed Francisco, or another member of the Rojas family.

Memling also painted two portraits of Bruges patricians: the 1480 Portrait of a young woman and the Diptych of Maarten van Nieuwenhove from 1487. Moreover, Maarten van Nieuwenhove was not just any ordinary citizen of Bruges; in 1497, he became mayor of the city and, after taking office, became part of Maximilian of Austria’s entourage.

The Portrait of a young woman is sold in Bruges in the 17th century and later donated to St Julian’s Hospital. In the 17th century, the Van Nieuwenhove family also gifted the Diptych of Maarten van Nieuwenhove to St Julian’s Hospital. Following the hospital’s closure, both paintings end up in Saint John’s Hospital in 1815.

1484: Moreel triptych

In 1484, Memling finishes an altarpiece commissioned by Willem Moreel. An important politician in Bruges, Willem needed an altarpiece for his private chapel in St James’s Church. Among other things, he is a director of Banco di Roma, a respected city official and mayor. The triptych depicts him together with his wife, sixteen of their eighteen children, and their patron saints.

1482 – 1489: The Saint Ursula Reliquary

Memling made the St Ursula Shrine at the request of the friars and nuns of Saint John’s Hospital. The previous shrine dates from around 1400–1415. The new shrine is a gilded reliquary whose panels are painted by Memling. On 21 October 1489, the feast day of Saint Ursula, the old St Ursula shrine in the choir of the hospital chapel is replaced by the new shrine. The side panels depict six scenes from Ursula’s pilgrimage, three on each long side.

19th century: Museum Sint-Janshospitaal

1839 and 1958: Saint John’s Hospital and its museum context

The works that Memling produces for Saint John’s Hospital are closely related to the lives of the friars and nuns. The St Ursula Shrine remains on display in the hospital chapel until the 20th century. The St John Altarpiece stands on the main altar of the same chapel until 1637, but under the French regime it is taken to Paris. In this period, the management of the hospital and other benevolent institutions is transferred to the Commissie van de Burgerlijke Godshuizen (“Commission of Civil Almshouses”). The altarpiece does not return to Saint John’s Hospital until 1815. That same year, the Diptych of Maarten van Nieuwenhove and the Portrait of a young woman also move to Saint John’s Hospital for the first time.

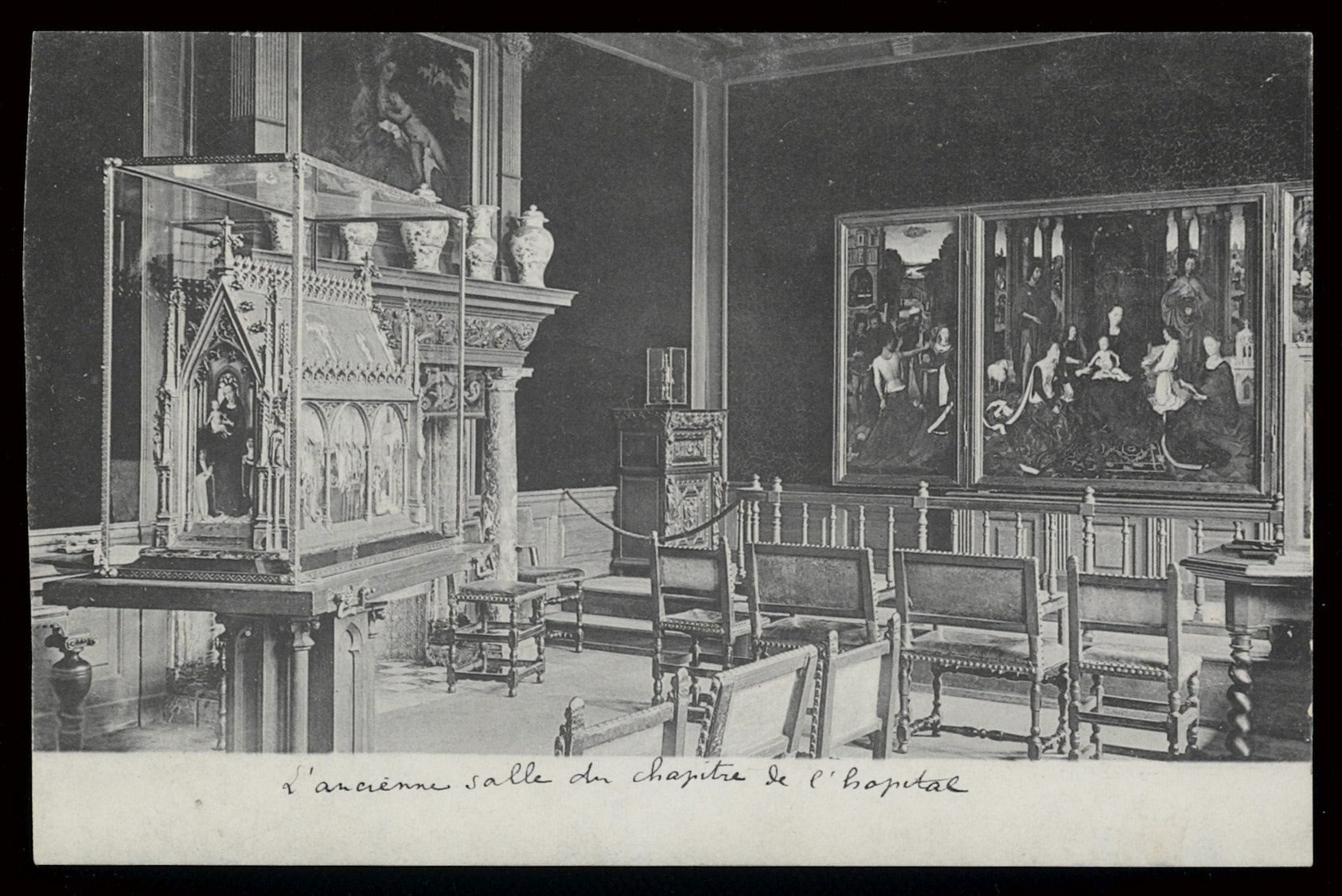

At that time, the chapter house collection can only be visited by appointment. But due to growing interest in the paintings, an alternative has to be sought. In 1839, after the St Ursula Shrine is also transferred to the chapter house, the room is opened to the public. We can therefore speak of the creation of Saint John’s Hospital’s first museum from 1839. Visitors can visit the painting room daily, except on Sundays and holidays. Thanks to preserved visitors registers, today we can still trace who visited Saint John’s Hospital. These registers came about because of a royal visit in 1843 by England’s Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. From then on, in addition to prominent figures, everyday visitors could also sign the register. This is how we know that painters such as Gustave Courbet, Georges Seurat, Paul Gauguin and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec also visited the collection.

The painting room’s collection continues to grow. But this means that Memling’s works are no longer the highlight for visitors. Consequently, the monastics decide to remove the other paintings from the chapter house. The architect Louis Delacenserie (1838–1909), who is in charge of the restoration of the hospital buildings at this time, is commissioned to renovate the interior of the old chapter house as well. The museum reopens in April 1891 as a ‘Memling museum’, exclusively for Memling’s oeuvre.

During the Second World War, the Memlings are forced to leave Bruges. In June 1942, the panels and the shrine are moved to the Castle of Lavaux-Sainte-Anne. Two years later, in June 1944, Memling’s works are transferred to the bank vaults of the Société Générale de Belgique in Brussels. They only returned to Saint John’s Hospital on 17 May 1945. After the war, the chapter house no longer had the necessary space to receive visitors. From 1958, the year of the World Exhibition, the former hospital wards are set up as a museum. Later, the attic is also given a museum function.

19th century: Revival

19th century: Reappraisal

Over time, Memling’s oeuvre becomes somewhat forgotten. Hardly any attention is paid to his work in the 17th century. In the 19th century, there is a general reappraisal of painting from the 15th and 16th centuries.

1794 and 1815: French rule

In 1794, the French occupiers close churches and monasteries. They confiscate works of art and the most important pieces are taken to Paris. Napoleon puts them on show, together with stolen artworks from other countries. The Musée Central is renamed ‘Musée Napoléon’ after 1799. The museum’s large number of religious artworks attracts many art lovers. The German philosopher Schlegel writes about the Musée Napoléon’s magnificent collection in international journals. His texts on ancient art are widely circulated.

The defeat of the French army at Waterloo (1815) plays an indirect role in the rediscovery of the Flemish Primitives. The Musée Napoléon is all but emptied and the works are returned to their rightful owners. Because a number of ecclesiastical institutions have meanwhile been destroyed or abolished, several works of art must find another home. For instance, the Municipal Academy of Bruges receives the works from the demolished St Donatian’s Cathedral. One of these works is the Moreel Triptych.

1830: Newly born Belgium

The reappraisal of painting from the 15th and 16th centuries is given impetus thanks to the national sentiment that develops after 1830 in the newly born Belgium. The hope is that imbuing Flemish art with a nationalistic function will emphasize Belgium’s cultural importance.

1867: James Weale

In 1855, the Englishman William Henry James Weale (1832–1917) arrives in Bruges. Weale shows a keen interest in the preservation of religious art. At that time, there is little academic knowledge about painting from the Low Countries. This situation is not even changed by several masterpieces going on display in the Musée Napoléon. According to Waele, better knowledge of the works goes hand in hand with an increasing appreciation of them. He publishes about the works in, among others, the Journal des Beaux-Arts and, in 1861, he writes the ‘Catalogue du Musée de l’Académie de Bruges. Notices, et descriptions avec monogrammes, etc.’ This catalogue of the Museum of the Bruges Academy earned Weale an international reputation as an art connoisseur. In 1867, together with Jules Helbig and Canon Jean de Béthune, he organizes the first ‘Tableaux de l’ancienne Ecole néerlandaise’ exhibition in the halls of the Belfry of Bruges.

20th century: Retrospective exhibitions

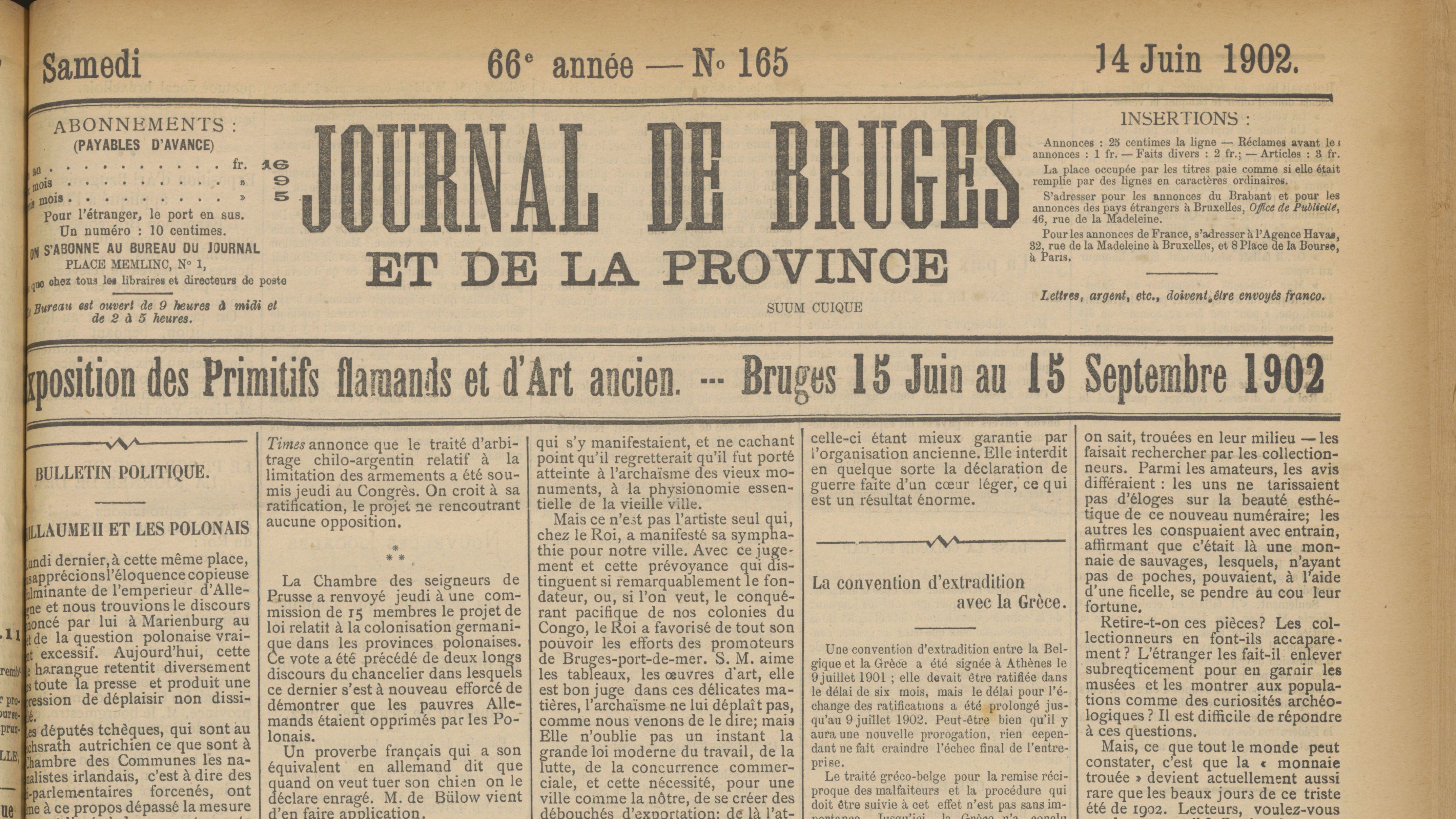

1902: l’Exposition des Primitifs flamands

In 1902, the Provincial Court becomes the setting for a large exhibition dedicated to the Flemish Primitives. The Memling Museum makes its masterpieces available for the event. It is not entirely coincidental that the exhibition takes places in Bruges. Originally, Philogène Wytsman wants to organize the expo in Brussels, but the City of Bruges refuses to loan its works.

By bringing together 413 works from the 15th and 16th centuries, the exhibition organizers hope that considerable new knowledge and insights about the works will emerge. For the first time, works of art attributed to the same artist will be displayed alongside each other. Consequently, it becomes clear that some attributions are in urgent need of revision.

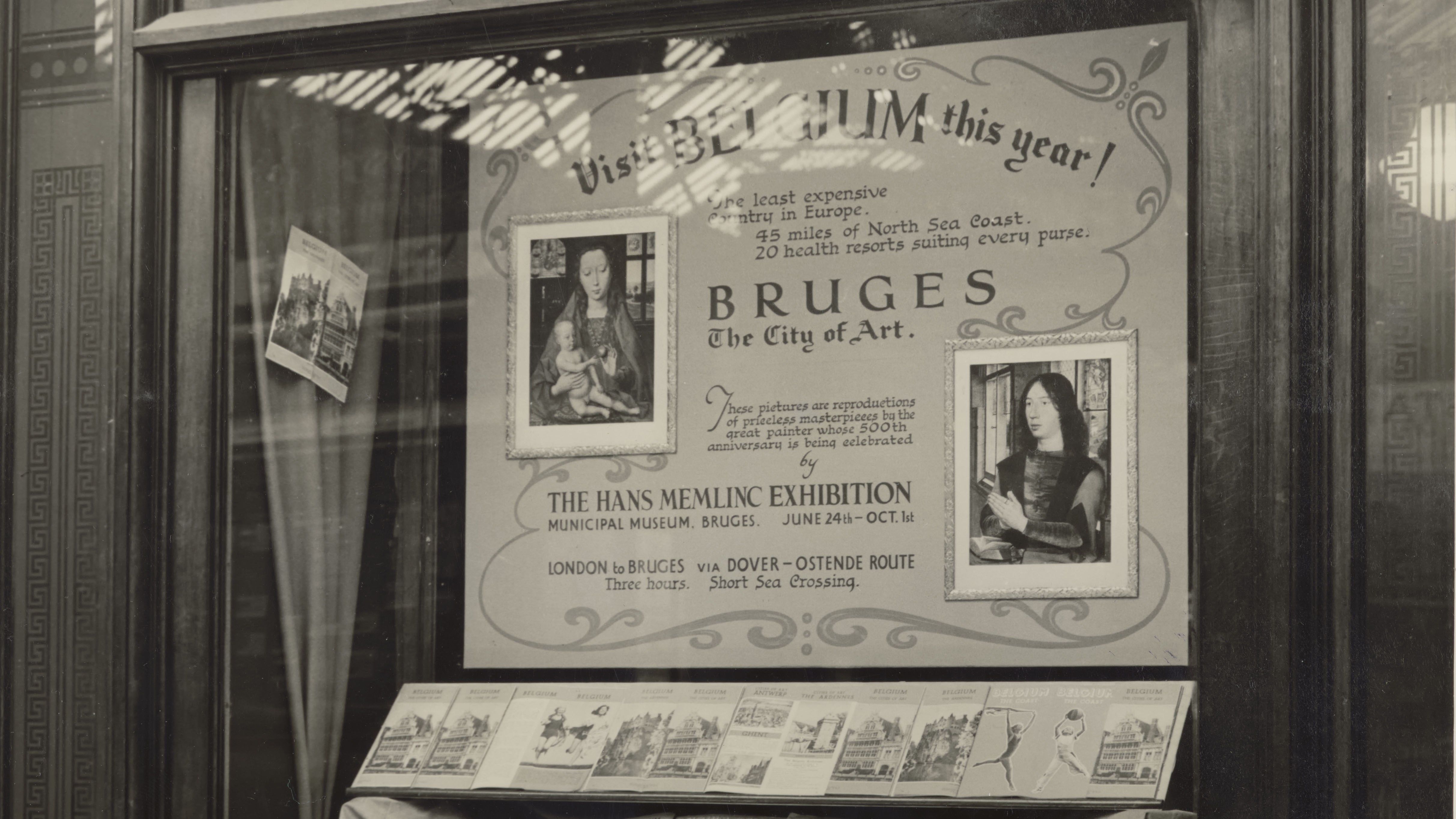

1994: ‘Hans Memling’

Retrospective exhibitions like the one in 1902 are a tradition in Bruges. Examples of the most important old painting exhibitions in Bruges include ‘Maîtres Anciens’ (1905), ‘Hans Memling’ (1939), and ‘De eeuw der Vlaamse Primitieven’ (The age of the Flemish Primitives) (1960). In 1994, five hundred years after his death, Bruges’s Groeningemuseum organizes a monographic exhibition on Memling. The exhibition is crucial for the reappraisal of Memling’s oeuvre.